As I write this, there is a large pandemic of coronavirus spreading across. Congratulations if you are lucky enough to read this article several years in the future!

I’m a biologist with a special geekiness towards ecology and evolution. What else should I write about if not the evolution of viruses?

What are viruses

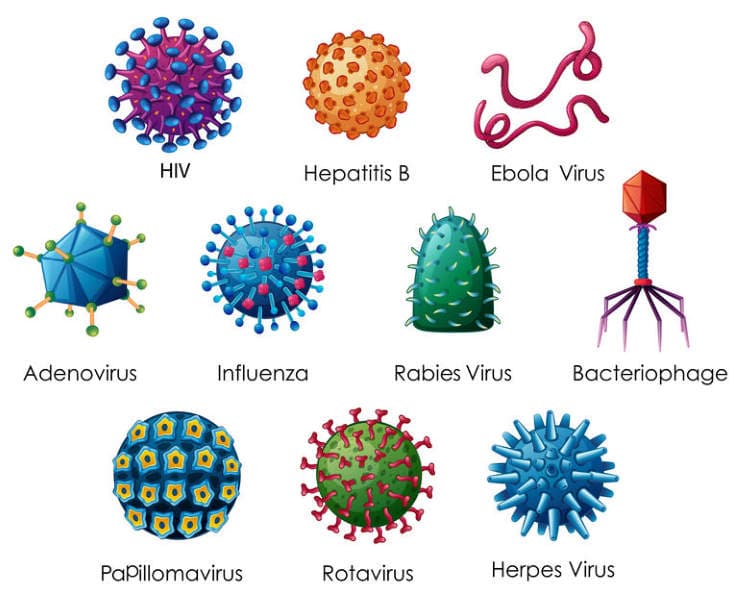

A virus essentially is genetic information in a capsule. That’s the blandest explanation I could come up with, but it works. Are viruses alive? The current consensus is that they are somewhere in between. They are not alive because they lack several properties of life, such as cellular organelles or metabolism, yet viruses are not non-living either, as they do share some life-like properties. For example, replication and evolution.

Evolution has lead to a large diversity of viruses around us. Don’t be alarmed, though. We tend to think about viruses as something bad, yet, the majority of them are harmless to us. For example, most viruses of other animals can’t hurt us. We can’t catch FIV (the cat equivalent of HIV) and we are completely out of reach of viruses that infect plants. But there is more. There are also viruses that infect bacteria, and, hell yeah, there are viruses that infect other viruses.

In our immediate interest, of course, are viruses that infect humans. Equally interesting are also ones that infect other animals but potentially could evolve an ability to infect us.

You probably have heard that the current coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 originally comes from bats after an evolutionary change that allowed it to infect us, as well. Evolution is also the reason why flu comes to us in a new shape each season or why HIV is now becoming resistant to previously established treatments. So, the question is how this happens.

How do viruses evolve

Genetic mutations

In essence, viruses evolve in the same way as any other organism does. All the basic rules of evolution apply. Whenever there is genetic information, mutations or errors in a copied genetic material can sneak in. Since genes determine traits, genetic mutations can lead to new abilities of viruses. For example, a virus with a new mutation (or a set of mutations) can gain the ability to infect a new species. Alternatively, a mild virus can gain some new characteristics and become severe.

What’s worse, many viruses evolve rapidly. Why so? That is because they store their genetic information differently than we do, and this way of storing has a higher mutation rate. Most living things have DNA as their primary genetic storage system, yet many viruses store their information in RNA.

What are DNA and RNA? You do not need to worry about that to understand this article. Long story short: our bodies store genetic information in DNA and use RNA as an intermediate product to build stuff that it needs.

When we or our cells replicate, our body has to copy all of our DNA; when viruses replicate, all of their RNA gets replicated. DNA replication involves spell-check afterward, but RNA does not. Therefore, RNA viruses (for example, influenza, coronaviruses, rabies, and more) tend to mutate and evolve on a lot quicker basis than DNA based organisms. Up to millions of times quicker.

For comparison, humans and chimps are separated by independent 6 million years of evolution and are recognizably different. Imagine a similar degree of evolutionary changes happening a million times faster—in a mere six years. It’s hard to imagine, but this is how fast some viruses evolve.

However, that is only the tip of the iceberg. Some viruses, such as influenza, coronaviruses, and others, have an additional trick up their sleeves.

Reassortment

When two strains of viruses, such as flu virus, infect the same host, their replication, metaphorically speaking, starts to happen on the same assembly lines. That creates a mixup.

To illustrate, imagine yourself putting together cars randomly choosing parts from two different models. You probably won’t create a car with two steering wheels, yet a car with a steer from one model and lamps from the other would not be a rarity. As a result, your garage would fill with a line of unique, one in the world, cars. Becasue of part compatibility, some of them, or even many, may not be able to drive. Yet a tiny fraction may turn out brilliant.

Similar stuff goes on with viruses, and it is especially common with influenza viruses and is the core reason why we see new strains so often.

![]()

When an animal gets infected with two or more strains of a virus, news strains are likely to show up. Most of them will be defunct, yet some, and one in a billion is more than enough, will have new superpowers.

This is, in fact, a mechanism of how new swine flu strain, that was able to infect humans emerged in 2009, and likely how a novel coronavirus emerged from bats.

Are viruses evolving into more dangerous forms?

In general, viruses do not evolve to be more dangerous. I fact, the death toll of different pandemics shows to gradually decrease since the middle ages.

The problem of why we perceive diseases as more dangerous is that viruses spread very well today. Why? Becasue our way of living gives them opportunities to spread. And that isn’t really news.

- Black Death, though caused not by a virus, came to Europe with merchant ships. Before they started to travel all across the world to and from Europe, plague had no chance at all to go pandemic.

- Spanish flu peaked during world war one—a war that the world had never seen before. Crowded trenches and ports, and massive transportation of troops were perfect conditions for the virus to spread.

- Quite recent outbreaks, such as SARS, MERS and current COVID-19, are mainly to blame becasue we live in a way they find it so easy to spread. I can board a plane in Europe and be in North America in less than ten hours. But that isn’t everything.

Not only have we made spreading of viruses easier, but we also have created a perfect environment for their evolution. Novel viruses that visit us come from the animal kingdom. Birds, pigs, and bats are recent examples, and we have made these animals vulnerable to infections.

The way we grow and keep our chickens is a land of happiness for viruses, and wild animals are not much safer, either. We have destroyed and shrank their habitats. Their populations, though declining, are squeezed into ever smaller territories, and their contacts with us are unavoidable. We also hoard and poach wild animals, which give viruses of these species more and more opportunities to find their ways to new parts of the world and us.

Is it all as grim as I stated? Well, I’d like to hope that it isn’t. Yet, the periodicity at which novel virus strains visit us, makes me think that more will come in the future. Unless, of course, we change some of our ways.

![]() Dive deeper into the world of viruses

Dive deeper into the world of viruses

Learn how viruses aided the beginning of life, why Covid-19 was nothing but a surprise, and how we can use viruses for our own benefit.

Read: “A Planet of Viruses” by Carl Zimmer

disclaimer: I earn a commission if you buy this book through my link.